Exclusive: United States Fast Tracks Proposal to Change WHO Rules on International Health Emergency Response

In the wake of the chaotic, and often failed, global response to the COVID pandemic, the United States is not waiting for an elaborate international treaty or convention on future pandemics, which will take years to negotiate.

Instead, Washington wants to fast track a series of nitty-gritty, but far- reaching changes in the existing International Health Regulations that govern WHO and member state emergency alert and response – for consideration at this year’s World Health Assembly, 22-28 May.

The US proposal for major IHR rule changes, obtained by Health Policy Watch, has been a topic of discussion in a series of closed-door meetings of WHO member states, which are considering ways to reform the existing IHR, as well as advancing a whole new WHO convention or other international instrument on pandemic prevention and response.

The US proposal, delivered to WHO’s Director General Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus in late January, is also featuring in the agenda of US Health and Human Services Assistant Secretary for Global Affairs, Loyce Pace, currently on a visit to Geneva. See related Health Policy Watch story.

The US is expected to lead a parallel track of tightly-paced “informal” member state negotiations to reach consensus on an IHR reform resolution for approval at this year’s 75th WHA, which is only three months away.

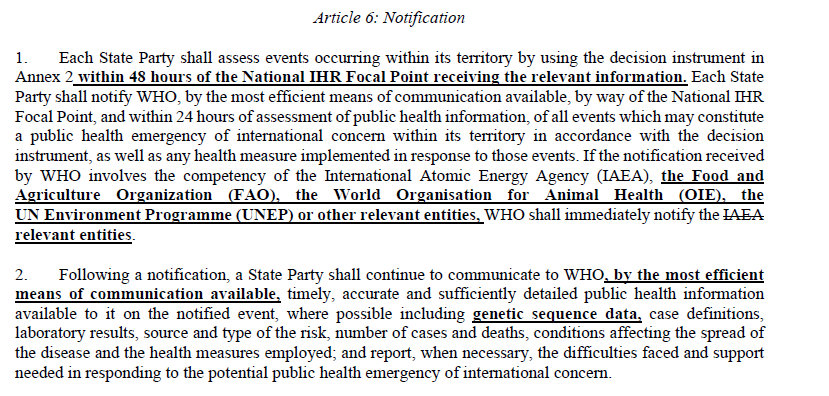

The US proposals are presented as a detailed series of text additions and deletions in the 2005 IHR rules. The amendments set out more defined criteria, terms and timelines for alerts, notification, and response to emerging disease threats or outbreaks. The proposed rule revisions clearly aim to “incentivise” countries to collaborate more closely with expert WHO pathogen SWAP teams in the event of an emerging threat – while avoiding an outright requirement.

The proposed rules also specifically ask member states to share the “genetic sequence data” of suspect pathogens right away.

And they call for WHO to develop new “early warning criteria for assessing and progressively updating the national, regional or global risk posed by an event of unknown costs or sources.” Such criteria, would in turn, better define, member state’s responsibilities for both monitoring and rapidly reporting on threats.

US initiative breaks taboo about reforming IHR

It’s unclear how the top WHO echelon will react to the changes – which have not yet been posted by WHO in the online agenda for the 75th WHA meeting, 22-28 May.

Notably, Tedros has been personally identified with advancing negotiations on a much broader multilateral instrument, such as a new pandemic convention or treaty. That approach also ahs been backed by a large bloc of European states, and it received conditional approval in a special WHA session last year, including lukewarm US support.

So In contrast to the grand political vision and extended timeline of a new accord, digging into a set of very prescriptive revisions to the IHR, may, in fact prove to be more politically difficult for WHO’s leadership.

That is particularly the case since major member states, notably Russia and China, are already at odds with the US over geopolitical issues ranging from the Ukraine to Taiwan. And even in normal times, they and other more authoritarian regimes would likely balk at any US initiative that creates stronger compliance mechanisms – perceived as an infringement on sovereignty.

Quiet welcome from WHO insiders

But as a set of practical proposals to address the real problems that the pandemic has laid bare, the US move may be quietly welcomed by many WHO insiders – as well as European and other allies. Civil society groups have also been cynical about the ambitions around a new multilateral treaty instrument – worrying about the excessive time and energy such negotiations might entail.

“Overall, I am happy that the US has proposed these amendments because it breaks this surreal dogma that has been in WHO for the past ten years, that the IHR should never be amended,” said one former WHO official, speaking to Health Policy Watch on condition of anonymity.

“The US took the initiative, and said there are flaws in the design, let’s change the design,” the former official added.

By submitting it to WHO formally in January, the US has ensured that the reform proposals must be put on the WHA agenda already in May, and be publicly debated there: “So clearly the US wants to put pressure. It wants to go quickly to get some kind of agreed package.

“I think there will be push back on this ‘draconian’ timeline for alert and notification,” the former official added. “But the purpose is good. It’s a way to increase transparency.

WHO empowered to share information about risks within 48 hours

The US proposal creates a series of clear timelines and trigger points regarding the responsibilities of a member state with a suspected disease threat to notify WHO – and WHO to notify other member states – both within a framework of two days each.

Significantly, member states would be required to inform WHO about emerging threats identified by its national IHR focal point within 48 hours, and then accept any WHO offer to “collaborate” on further assessment.

WHO, in turn, would be mandated to make widely available within 48 hours the information it has about a significant emerging – if the member state rejects the collaboration.

“If the State Party does not accept the offer of collaboration within 48 hours, WHO shall, when justified by the magnitude of the public health risk, immediately share with other States Parties the information available to it, whilst encouraging the State Party to accept the offer of collaboration by WHO,” states the proposed amendment to Article10-4.

This, in contrast to existing language, which does not explicitly mandate collaboration with WHO on threats, and requires open-ended WHO “consultations” before the Agency even makes available information about emerging threats to other member states or the public- something that currently delays notifications for weeks and months.

‘Yellow light’ – Regional and intermediate public health emergency warnings

The rules also would give WHO the authority to declare a public health emergency threat at the intermediate and regional level – rather than only globally – as it does now.

Creation of a kind of “yellow” warning light before declaration of a full-scale global emergency has long been discussed in connection with the SARS-COV-2 pandemic, as a measure that could have alerted countries earlier about risks of the fast-spreading coronavirus infection in the first weeks – even when the epidemic remained geographically confined to Asia.

And in the case of other emergencies, such as the West African 2014 Ebola outbreak, and prior coronavirus outbreaks of MERS in the Middle East as well as the first 2003 SARS outbreak in Asia – a much more regional spread of pathogens was more immediately obvious than the dynamics of global transmission.

Finally, the amendments would create an IHR “compliance” committee for monitoring member states’ adherence to the IHR rules, which are legally binding. A compliance mechanism, a standard feature of most international treaties, has been a gaping omission in the existing IHR system, observers say.

Proposal on table of WHO talks this week

While Washington has provided support, in principle, to a new pandemic convention or other multilateral accord, it has never been as enthusiastic about the proposal as Europe, noting that it will take years to negotiate. Preliminary deliberations by a a new Intergovernmental Negotiating Body, which begn Thursday (February 24) are set to continue through June 2023 – and would only come before the WHA in 2024.

In contrast, the US proposal on IHR reform would already go before the World Health Assembly at its upcoming May session, as per the letter from the US Mission in Geneva to the WHO Director General 20 January 2022 – noting that its submission to the WHA agenda was made within the four-month deadline. .

The US message to the WHO DG underlined, “the critical importance of strengthening the IHR (2005) along with other efforts to strengthen the ability of the WHO and Member States to prevent, detect and respond to future public health emergencies of international concern.”

Pace, when asked for her take on the IHR reform proposal, at a media briefing Wednesday at the US Mission in Geneva, said:

“We really tried to skim off what we thought would be the most critical enhancements that could be made. In terms of what they entail, whether we are talking about improved alert systems or other components, some of the issues are maybe tougher to tackle than others.

“I think what is encouraging for us is that we had close to 50 member states signing onto this approach. We are really quite hopeful that we will see success in this effort, sooner rather than later.”

But Pace acknowledged that the first real litmus test of the US initiative will be Thursday, at the initial formal session of a new “Intergovernmental Negotiating Body” on pandemic response reform: “When it comes to the instruments of this process, we are really mindful of the process kicking off tomorrow.”

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)