When the Globalists Crossed the Rubicon: The Assassination of Shinzo Abe

All Global Research articles can be read in 51 languages by

activating the “Translate Website” drop down menu on the top banner of

our home page (Desktop version).

To receive Global Research’s Daily Newsletter (selected articles), click here.

Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

***

To read this article in Japanese, click the Translate Website drop down menu

この記事を日本語で読むには、ウェブサイトの翻訳ドロップダウンウェブサイトをクリックしてください。

***

July 8 was a muggy day in the ancient capital of Japan. Shinzo Abe,

the most powerful figure in Japanese politics, was delivering a stump

speech for a local Liberal Democratic Party candidate in front of the

Nara Kintetsu railway station when suddenly a loud bang rang out,

followed by an odd cloud of smoke.

The response was incredible. Among those in the unusually large crowd

gathered, not a single person ran for cover, or hit the ground in

terror.

Abe’s body guards, who stood unusually far away from him during the

speech, looked on impassively, making no effort to shield him, or to

pull him to a safe location.

A few seconds later, Abe crumpled and collapsed to the ground, lying

there impassive in his standard blue jacket, white shirt, now speckled

with blood, and trademark blue badge of solidarity with Japanese

abductees in North Korea. Most likely he was killed instantaneously.

Only then did the body guards seize the suspect, Yamagami Toruya,

who was standing behind Abe. The tussle with Yamagami took the form of a

choreographed dance for the television audience, not a professional

takedown.

Yamagami was immediately identified by the media as a 41-year-old

former member of the Maritime Self-Defense Force who had personal

grievances with Abe.

Yamagami told everything to the police without hesitation. He did not

even try to run from the scene and was still holding the silly

hand-made gun when the bodyguards grabbed him.

Even after Abe was lying on the pavement, not a single person in the

crowd ran for shelter, or even looked around to determine where the

shots came from. Everyone seemed to know, magically, that the shooting

was over.

Then the comedy began. Rather than putting Abe in a limousine and

whisking him away, those standing around him merely called out to

passersby, asking if anyone was a doctor.

The media immediately embraced the “lone gunman” conclusion for this

attack, repeating entertaining tale of how Yamagami was associated with

Toitsu Kyokai, a new religion started by the charismatic shaman Kawase

Kayo, and why he blamed Abe, who had exchanges with that group, for his

mother’s troubles.

Because Toitsu Kyokai has followers from the Unification Church

founded by Reverend Moon Sun Myung, journalist Michael Penn jumped to

the conclusion that the conspiracy leading to Abe’s death was the result of his collaboration with the Moonies.

Although the mainstream media accepted this fantastic story, the

Japanese police and security apparatus did not manage to squash

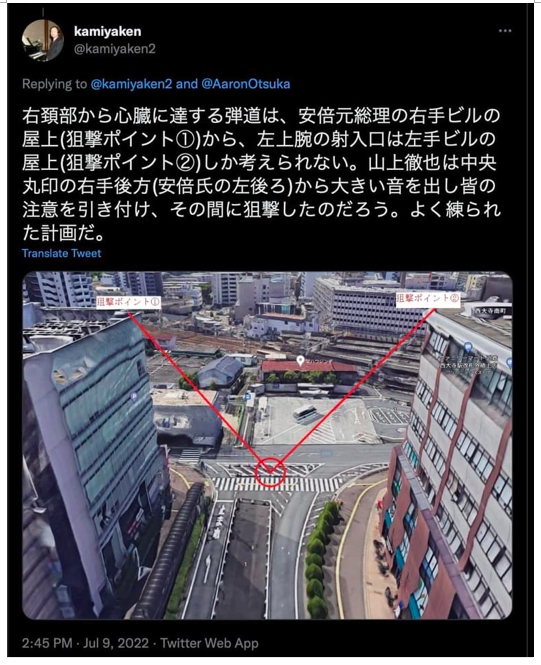

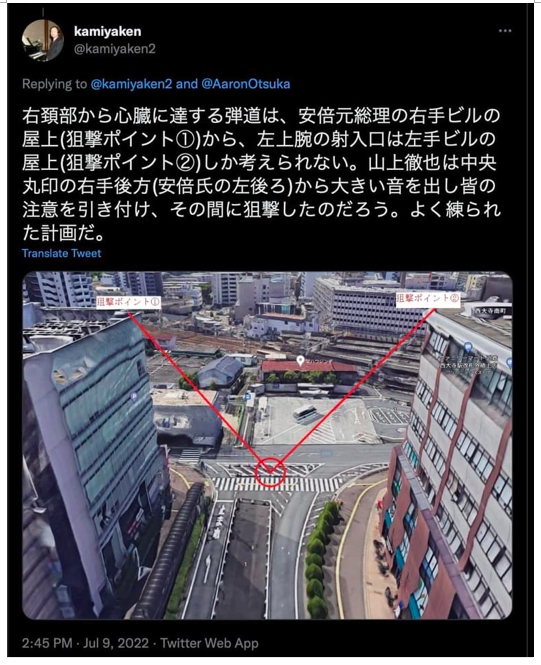

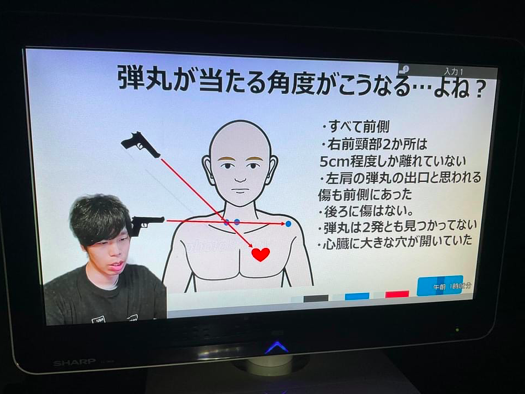

alternative interpretations. Blogger Takashi Kitagawa

posted materials on July 10 that suggested Abe was shot from the front,

not from the back where Yamagami stood, and that the shots must have

been fired at an angle from the top of one, or both, of the tall

buildings on either side of the intersection across from the railway

station plaza.

Takahashi Kitakawa’s postings:

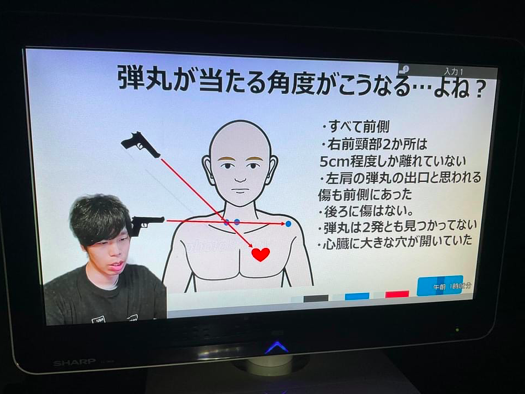

Kitagawa’s analysis of the paths of the bullets was more scientific than anything offered by the media that had claimed, without basis, that Abe had only been shot once until the surgeon announced that evening that there had been two bullets.

The chances that a man holding an awkward home-made gun, standing

more than five meters away in a crowd, would be able to hit Abe twice

are low. The TV personality Kozono Hiromi, who is a gun expert himself,

remarked on his show “Sukkiri” (on July 12) that such a feat would be incredible.

A careful viewing of the videos suggests that multiple shots

were fired by a rifle with a silencer from atop a neighboring building.

安倍晋三元総理大臣暗殺について 言明します from Emanuel Pastreich on Vimeo.

The message to the world

For a figure like Shinzo Abe, the most powerful political player in

Japan and the person to whom Japanese politicians and bureaucrats

rallied in response to the unprecedented uncertainty born of the current

geopolitical crisis, to be shot dead with no serious security detail nearby makes no sense.

Perhaps the message was lost on viewers at home, but it was crystal

clear for other Japanese politicians. For that matter, the message was

clear for Boris Johnson, who was forced out of power at almost exactly the same moment that Abe was shot, or for Emmanuel Macron,

who was suddenly charged with influence peddling scandal for Uber, and

faces demands for his removal from office, on July 11—after months of

massive protests had failed to sway him in any way.

The message was written all over Abe’s white shirt in red: buying

into the globalist system and promoting the COVID-19 regime is not

enough to assure safety, even for the leader of a G7 nation.

Abe was highest ranking victim so far of the hidden cancer eating

away at governance in nation states around the world, an institutional

sickness that moves decision making away from national governments to a

network of privately-held supercomputer banks, private equity groups,

for-hire intelligence firms in Tel Aviv, London and Reston, and the

strategic thinkers employed by the billionaires at the World Economic

Forum, NATO, the World Bank and other such awesome institutions.

The fourth industrial revolution was the excuse employed to transfer

the control of all information in, and all information out, for central

governments to Facebook, Amazon, Oracle, Google, SAP and others in the

name of efficiency. As J. P. Morgan remarked, “Everything has two

reasons: a good reason and a real reason.”

With the assassination of Abe, these technology tyrants, and their

masters, have crossed the Rubicon, declaring that those dressed in the

trappings of state authority can be mowed down with impunity if they do

not follow orders.

The Problem with Japan

Japan is heralded as the only Asian nation advanced enough to join

the “West,” to be a member of the exclusive G7 club, and to be qualified

to enter into collaboration with (and possible membership in) the top

intelligence sharing program, the “Five Eyes.” Nevertheless, Japan has

continued to defy the expectations, and the demands, of global

financiers, and the planners within the beltway and on Wall Street for

the New World Order.

Although it was South Korea in Asia that has constantly been berated

in Washington as an ally not quite up to the level of Japan, the truth

is that the super-rich busy taking over the Pentagon, and the entire

global economy, were starting to harbor doubts about the dependability

of Japan.

The globalist system at the World Bank, Goldman Sachs, or the Belfer

Center for Science and International Affairs at Harvard University has a

set track for the best and the brightest from “advanced nations.”

Elites from Australia, France, Germany, Norway or Italy, learn to

speak fluent English, spend time in Washington, London, or Geneva at a

think tank or university, secure a safe sinecure at a bank, a government

institution, or a research institute that assures them a good income,

and adopt the common sense, pro-finance, perspective offered by the

Economist Magazine as the gospel.

Japan, however, although it has an advanced banking system of its

own, although its command of advanced technologies makes it the sole

rival of Germany in machine tools, and although it has a sophisticated

educational system capable of producing numerous Nobel Prize winners,

does not produce leaders who follow this model for the “developed”

nation.

Japanese elite do not study abroad for the most part and Japan has

sophisticated intellectual circles that do not rely on information

brought in from overseas academic or journalistic sources.

Unlike other nations, Japanese write sophisticated journal articles

entirely in Japanese, citing only Japanese experts. In fact, in fields

like botany and cellular biology, Japan has world-class journals written

entirely in Japanese.

Similarly, Japan has a sophisticated domestic economy that is not

easily penetrated by multinational corporations—try as they do.

The massive concentration of wealth over the last decade has allowed

the super-rich to create invisible networks for secret global

governance, best represented by the World Economic Forum’s Young Global

Leaders program and the Schwarzman Scholars program. These rising

figures in policy infiltrate the governments, the industries, and

research institutions of nations to make sure that the globalist agenda

goes forth unimpeded.

Japan has been impacted by this sly form of global governance. And

yet, Japanese who speak English well, or who study at Harvard, are not

necessarily on the fast track in Japanese society.

There is stubborn independence in Japan’s diplomacy and economics,

something that raised concerns among the Davos crowd during the COVID-19

campaigns.

Although the Abe administration (and the subsequent Kishida

administration) went along with the directives of the World Economic

Forum and the World Health Organization for vaccines and social

distancing, the Japanese government was less intrusive in the lives of

citizens than most nations, and was less successful in forcing

organizations to require vaccination.

The use of QR codes to block service to the unvaccinated was limited

in its implementation in Japan in comparison with other “advanced”

nations.

Moreover, the Japanese government refuses to fully implement the

digitalization agenda demanded, thus denying multinational technology

giants the control over Japan that they exercise elsewhere. This lag in

Japan’s digitalization led the Wilson Center in Washington D.C. to

invite Karen Makishima,

minister of Japan’s Digital Agency (launched under pressure from global

finance in September, 2021) so that she could explain why Japan has

been so slow to digitalize (July 13).

Japanese are increasingly aware that their resistance to

digitalization, to the wholescale outsourcing of the functions of

government and university to multinational tech giants, and the

privatization of information, is not in their interest.

Japan continues to operate Japanese-language institutions that follow

old customs, including the use of written records. Japanese still read

books and they are not so enamored with AI as Koreans and Chinese.

Japan’s resistance can be traced back to Meiji restoration of 1867.

Japan set out to create governmental system wherein Western ideas were

translated into Japanese, combined with Japanese concepts, to create a

complex domestic discourse. The governance system set up in Meiji

restoration remains in place to a large degree, using models for

governance based on pre-modern principles from Japan and China’s past,

and drawn from 19th century Prussia and England.

The result is feudalistic approach to governance wherein ministers

oversee fiefdoms of bureaucrats who carefully guard their own budgets

and who maintain their own internal chains of command.

The Problem with Abe

Shinzo Abe was one of the most sophisticated politicians of our age,

always open to make a deal with the United States, or other global

institutions, but always cagy when it came to making Japan the subject

of globalist dictates.

Abe harbored the dream of restoring Japan to its status as an empire,

and imagined himself to be the reincarnation of the Meiji Emperor.

Abe was different from Johnson or Macron in that he was not as

interested in appearing on TV as he was in controlling the actual

decision making process within Japan.

There is no need to glorify Abe’s reign, as some have tried to do. He

was a corrupt insider who pushed for the dangerous privatization of

government, the hollowing out of education, and who backed a massive

shift of assets from the middle class to the wealthy.

His use of the ultra-right Nihon Kaigi forum to promote an

ultranationalist agenda, and to glorify the most offensive aspects of

Japan’s imperial past, was deeply disturbing. Abe gave his unflinching

support for all military expenditures, no matter how foolish, and he was

willing to support just about any American boondoggle.

That said, as the grandson of Prime Minister Nobusuke Kishi, and the

son of foreign minister Shintaro Abe, Shinzo Abe showed himself to be an

astute politician from childhood. He was creative in his use of a wide

range of political tools to advance his agenda, and he could call on

corporate and government leaders from around the world with an ease that

no other Asian politician could.

I remember vividly the impression I received from Abe on the two

occasions that I met him in person. Whatever cynical politics he may

have promoted, he radiated to his audience a purity and simplicity, what

the Japanese call “sunao,” that was captivating. His manner suggested a

receptiveness and openness that inspired loyalty among his followers

and that could overwhelm those who were hostile to his policies.

In sum, Abe was sophisticated political figure who was capable of

playing one side against the other within the Liberal Democratic Party,

and within the international community, while appearing to be a

considerate and benevolent leader.

For this reason, Japanese hostile to Abe’s ethnic nationalism were

still willing to support him because he was the only politician they

thought capable of restoring global political leadership to Japan.

Japanese diplomats and military officers fret endlessly about the

Japan’s lack of vision. Although Japan has all the qualifications to be a

great power, they reason, it is run by a series of unimpressive,

University of Tokyo graduates; men who are good at taking tests, but are

unwilling to take risks.

Japan produces none like Putin or Xi, and not even a Macron or a Johnson.

Abe wanted to be a leader and he had the connections, the talent, and

the ruthlessness required to play that role on the global stage. He was

already the longest serving prime minister in Japanese history, and had

plans for a third bid as prime minister, when he was struck down.

Needless to say, the powers behind the World Economic Forum do not

want national leaders like Abe, even if they conform with the global

agenda, because they are capable of organizing resistance within the

nation state.

What went wrong?

Abe was able to handle, using the traditional tools of statecraft,

the impossible dilemma faced by Japan over the last decade as its

economic ties with China and Russia increased, but its political and

security integration with the United States, Israel and the NATO block

proceeded apace.

It was impossible for Japan to be that close to the United States and

its allies while maintaining friendly relations with Russia and China.

Yet Abe almost succeeded.

Abe remained focused and cool. He made use of all his skills and

connections as he set out to carve a unique space for Japan. Along the

way, Abe turned to the sophisticated diplomacy of his strategic thinker Shotaro Yachi of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to assure that Japan found its place under the sun.

Abe and Yachi used contradictory, but effective, geopolitical

strategies to engage both East and West, making ample use of secret

diplomacy to seal long-term deals that put Japan back in the great

powers game.

On the one hand, Abe presented to Obama and Trump a Japan that was

willing to go further than South Korea, Australia or other India in

backing Washington’s position. Abe was willing to suffer tremendous

domestic criticism for his push for a remilitarization that fit the US

plans for East Asia.

At the same time that he impressed Washington politicians with his

gung-ho pro-American rhetoric, matched by the purchase of weapons

systems, Abe also engaged China and Russia at the highest levels. That

was no small feat, and involved sophisticated lobbying within the

beltway, and in Beijing and Moscow.

In the case of Russia, Abe successfully negotiated a complex peace treaty

with Russia in 2019 that would have normalized relations and solved the

dispute concerning the Northern Territories (the Kuril Islands in

Russian). He was able to secure energy contracts for Japanese firms and

to find investment opportunities in Russia even as Washington ramped up

the pressure on Tokyo for sanctions.

The journalist Tanaka Sakai

notes that Abe was not banned from entering Russia after the Russian

government banned all other representatives of the Japanese government

from entry.

Abe also engaged China seriously, solidifying long-term institutional

ties, and pursuing free trade agreement negotiations that reached a

breakthrough in the fifteenth round of talks (April 9-12, 2019). Abe had

ready access to leading Chinese politicians and he was considered by

them to be reliable and predictable, even though his rhetoric was

harshly anti-Chinese.

The critical event that likely triggered the process leading to Abe’s assassination was the NATO summit in Madrid (June 28-30).

The NATO summit was a moment when the hidden players behind the

scenes laid down the law for the new global order. NATO is on a fast

track to evolve beyond an alliance to defend Europe and to become an

unaccountable military power, working with the Global Economic Forum,

the billionaires and the bankers around the world, as a “world army,”

functioning much as the British East India Company did in another era.

The decision to invite to the NATO summit the leaders of Japan, South

Korea, Australia and New Zealand was a critical part of this NATO

transformation.

These four nations were invited to join in an unprecedented level of

integration in security, including intelligence sharing (outsourcing to

big tech multinationals), the use of advanced weapons systems (that must

be administrated by the personnel of multinationals like Lockheed

Martin), joint exercises (that set a precedent for an oppressive

decision-making process), and other “collaborative” approaches that

undermine the chain of command within the nation state.

When Kishida returned to Tokyo on July first, there can be no doubt

that one of his first meetings was with Abe. Kishida explained to Abe

the impossible conditions that the Biden administration had demanded of

Japan.

The White House, by the way, is now entirely the tool of globalists

like Victoria Nuland (Under Secretary of State for Political Affairs)

and others trained by the Bush clan.

The demands made of Japan were suicidal in nature. Japan was to

increase economic sanctions on Russia, to prepare for possible war with

Russia, and to prepare for a war with China. Japan’s military,

intelligence and diplomatic functions were to be transferred to the

emerging blob of private contractors gathering for the feast around

NATO.

We do not know what Abe did during the week before his death. Most

likely he launched into a sophisticated political play, using of all his

assets in Washington D.C., Beijing, and Moscow—as well as in Jerusalem,

Berlin, and London, to come up with a multi-tiered response that would

give the world the impression that Japan was behind Biden all the way,

while Japan sought out a détente with China and Russia through the back

door.

The problem with this response was that since other nations had been

shut down, such a sophisticated play by Japan made it the only major

nation with a semi-functional executive branch.

Abe’s death parallels closely that of Seoul’s mayor Park Won Sun, who went missing on July 9th,

2020, exactly two years before Abe’s assassination. Park took steps in

Seoul City Hall to push back on the COVID-19 social distancing policies

that were being imposed by the central government. His body was found

the next day and the death was immediately ruled a suicide resulting

from his distress over charges of sexual harassment by a colleague.

What to do now?

The danger of the current situation should not be underestimated. If

an increasing number of Japanese come to perceive, as the journalist

Tanaka Sakai suggests, that the United States destroyed their best hope

for leadership, and that the globalists want Japan to make do with an

unending series of weak-minded prime ministers who are dependent on

Washington and other hidden players of the parasite class, such a

development could bring about a complete break between Japan and the

United States, leading to a political or military conflict.

It is telling that Michael Green, the top Japan hand in Washington

D.C., did not write the initial tribute to Abe that was published on the

homepage of CSIS (Center for Strategic and International Studies), his

home institute.

Green, veteran of the Bush National Security Council and Henry A. Kissinger Chair of the Asia Program at CSIS, is the author of Line

of Advantage: Japan’s Grand Strategy in the Era of Abe Shinzo. Green

was a close associate of Abe, perhaps the closest of any American.

The tribute to Abe was drafted by Christopher Johnstone (the Japan

chair at CSIS and former CIA officer). The weird choice suggests that

the assassination is so sensitive that Green instinctively wished to

avoid writing the initial response, leaving it to a professional

operative.

For responsible intellectuals and citizens in Washington, Tokyo, or

elsewhere, there is only one viable response to this murky

assassination: a demand for an international scientific investigation.

Painful as that process might be, it will force us to face the

reality of how our governments have been taken over by invisible powers.

If we fail to identify the true players behind the scenes, however,

we may be led into a conflict in which the blame is projected onto heads

of state and countries are forced into conflicts so as to hide the

crimes of global finance.

The loss of control of the Japanese government over the military the

last time can be attributed in part to the assassinations of prime

minister Inukai Tsuyoshi on May 15, 1932 and of prime minister Saito

Makoto on February 26, 1936.

But for the international community, the more relevant case is how

the manipulations of an integrated global economy by the Rothschild,

Warburg, and other banking interests created an environment wherein the

tensions produced by the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of

Austria-Hungary on June 28, 1914 were funneled towards world war.

*

Note to readers: Please click the share buttons above or below.

Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram

Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

Emanuel Pastreich served as the president of the

Asia Institute, a think tank with offices in Washington DC, Seoul,

Tokyo and Hanoi. Pastreich also serves as director general of the

Institute for Future Urban Environments. Pastreich declared his

candidacy for president of the United States as an independent in

February, 2020.