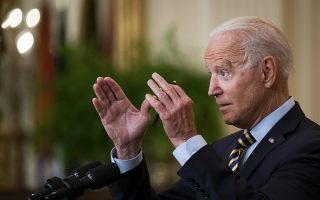

CRYSTAL LAKE, Ill. – Even President Joe Biden thought he had been ponderous.

“I know that’s a boring speech,” the 46th president said at the end

of 31 minutes and 19 seconds filled with statistics (2,374 Illinois

bridges), academic studies (on-site child care increases productivity),

global gross domestic product comparisons (China used to be No. 9, but

is now No. 2) and predictions of 7.4% economic growth (though “the OECD

thinks it could be higher,” Biden noted, referring to the not exactly

electrifying Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.)

The president’s remarks Wednesday, delivered to a friendly and

respectful crowd of supporters at McHenry County College in this Chicago

suburb, even included “reconciliation,” which Biden quickly admitted

was a “fancy” Washington word.

As the president travels the country pitching his plan for spending

trillions of dollars to reshape the American economy, he is facing a

rhetorical reality that has long plagued many of his predecessors: There

is a vast difference between explaining and inspiring, and Biden – who

was recently called the “explainer in chief” by his press secretary –

often struggles to reach the potential oratorical heights of the office

he holds.

Biden’s ambitions are vast and the substance of his presidency has

been dramatic at times: an end to the nation’s longest war, a historic

focus on equity and spending proposals bigger than anything before. He

sometimes describes his agenda as a way to prove that the very concept

of democracy itself can deliver for the people.

The White House is perfectly fine with Biden’s ability to turn down

the political heat in Washington after four years of chaotic governance.

But like former Presidents Barack Obama, who once delivered a 17-minute

answer to a health care question, and Bill Clinton, who was forced to

apologize to a late night comic for a dreadful convention speech, Biden

can sometimes get lost in the minutiae.

To be sure, the details of governing are mind-numbingly tedious. But

when the president starts a speech, what can seem like high-stakes drama

to those inside the Washington Beltway often feels like the stuff of

PBS documentaries to the rest of the country.

“There’s a loophole in the system called stepped up basis,” Biden

explained in excruciating detail Wednesday, laying out the case of a

wealthy person who owes taxes on the sale of a stock. “If on the way to

cash it in I get hit by a truck, God forbid, and died, it was left to my

daughter, there would be no tax paid. It’s not inheritance tax. It was a

tax due 10 seconds earlier!”

If it was hard for the audience to follow – the students and faculty

at McHenry sat silently most of the time – the details in Biden’s

speeches often trip him up as well, leading to mumbles, stumbles, pauses

and real-time corrections as he struggles through the dense material on

the teleprompter.

“We closed that loophole, and that saves us $400 billion a year – not

a year – $400 billion over this period,” Biden said as he fought his

way to the end of his lecture on the stepped-up basis loophole.

The president is not always boring. His passion and empathy can show

through in his remarks, often punctuated by his trademark whisper for

emphasis. And sometimes, the topic is just inherently compelling, as was

the case Thursday when he defended his decision to withdraw troops from

Afghanistan, ending America’s longest war.

In that speech, Biden spoke in powerful terms about the war’s place

in the arc of history, declaring that “the United States cannot afford

to remain tethered to policies creating a response to a world as it was

20 years ago.”

There were few such moments in Illinois. But the president is not

alone in finding it difficult to always deliver inspiring prose.

Obama’s discursive, 17-minute answer came during a health care town hall in 2010.

As The Washington Post reported, Obama “wandered from topic to topic,

including commentary on the deficit, pay-as-you-go rules passed by

Congress, Congressional Budget Office reports on Medicare waste, COBRA

coverage, the Recovery Act and Federal Medical Assistance Percentages

(he referred to this last item by its inside-the-Beltway name,

‘F-Map’).”

The lengthy answer prompted Obama to apologize to the audience at the end. “Boy, that was a long answer,” he said. “I’m sorry.”

Clinton was famous for boring speeches, too, delivering an hour-plus

State of the Union address in 1994 that was the longest since one by

Lyndon Johnson. And Clinton’s speech at the 1988 Democratic convention

to nominate Michael Dukakis for president was so long and awful – as he

later conceded – that Clinton appeared on “The Tonight Show Starring

Johnny Carson” to apologize for it.

“It just didn’t work. I mean, I know, what can I tell you?” Clinton,

then the governor of Arkansas, said after Carson put an hourglass on the

edge of his desk when the young politician started speaking. “My sole

goal was achieved,” Clinton joked. “I wanted so badly to make sure

Michael Dukakis was great, and I succeeded beyond my wildest dreams.”

But even compared with previous presidents, Biden has a long history of being long-winded.

He developed that skill in the Senate, where the idea of a political

filibuster is not only a literal legislative tool but a political

advantage for those – like Biden – who were good at talking, and

talking, and talking.

In 2006, a New York Times reporter described Biden’s interrogation of

Judge Samuel A. Alito Jr. during his confirmation hearing before the

Senate Judiciary Committee to be a Supreme Court justice.

“The highest ratio of words per panelist to words per nominee was

that of Senator Joseph R. Biden Jr., Democrat of Delaware, who managed

to ask five questions in his 30-minute time allotment,” the reporter

wrote.

Biden, the reporter added, “dived into a soliloquy on Judge Alito’s

failure to recuse himself from cases involving the Vanguard mutual fund

company, which managed the judge’s investments. After 2 minutes 50

seconds – short for the senator – Mr. Biden did appear to veer toward a

question, but abandoned it to cite Judge Alito’s membership in a

conservative Princeton alumni group. Mr. Biden discoursed on that for a

moment, then interrupted himself with an aside about his son who ‘ended

up going to that other university, the University of Pennsylvania.’”

In Washington, criticism most often comes from across the political

aisle. But on the subject of Biden’s penchant for pontificating, even

his closest allies have been known to notice.

During one hearing of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee in 2005,

Obama, then a young senator, grew exasperated during a lengthy

monologue by Biden, then the panel’s top Democrat.

“Shoot. Me. Now,” Obama wrote to an aide as Biden spoke.

The tendency toward long, detailed speeches did not fade as vice

president. And as a candidate for president, Biden was sometimes

criticized for not putting on display the same kind of powerful

performances that his rivals did.

Nowhere was that contrast more striking than with former President

Donald Trump, whose bellicose, rambling, he-could-say-anything speeches

were just as long – if not longer – than Biden’s but were rarely boring

in the traditional sense. (In 2016, as a candidate, Trump ejected a

MAGA-hat-wearing supporter who had the temerity to stand up during a

speech and declare, “This is boring!”)

Voters, it seems, decided to choose boring over bombast. And for that, Biden and his White House advisers make no apology.

In fact, even after acknowledging that his speech Wednesday had been

less than enthralling – even to him – Biden offered another admonition

to the audience in the room, and those watching on television.

It might have been a boring speech, he said, “but it’s an important speech.”

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.