The Social Conditions That Shaped Lola’s Story

Anakbayan USA, a national organization of Filipino youth and students dedicated to advancing democratic rights, sends this response:

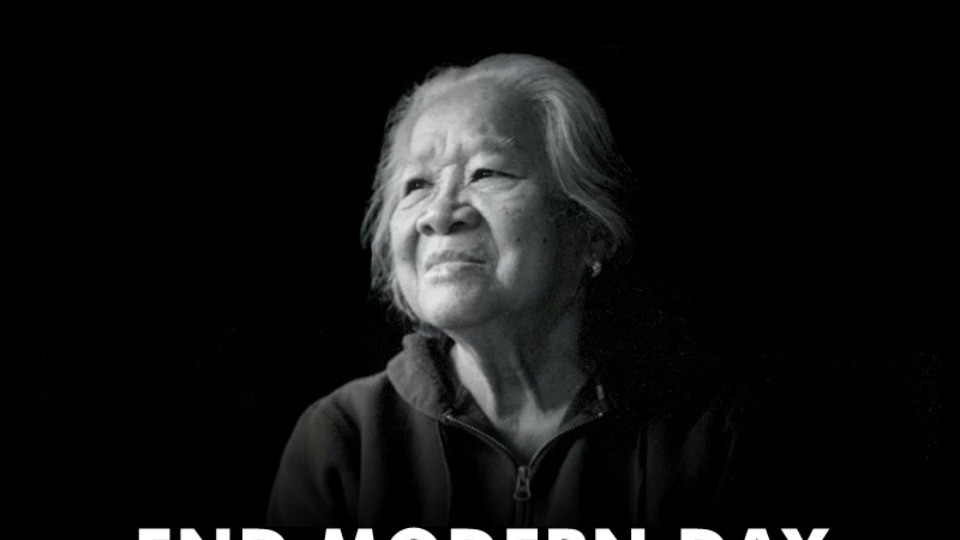

In the viral Atlantic article, “My Family’s Slave,” author Alex Tizon tells his account of Eudocia Tomas Pulido, who was to Tizon’s family both “Lola” and slave. Behind the heart-wrenching storytelling is a reality we must face: the oppressive class structures and culture that brought forth Eudocia’s enslavement and trafficking, and the need to change them in order to address the root of modern day slavery within the Filipino community.

The use of underpaid and overworked katulong, utusan, and kasambahay—the kind of servitude Eudocia was forced to perform—is common practice among many Filipino families. It is an unjust practice that stems from a violent history of colonization and exploitation of the Filipino people. In the Philippines, thousands of Filipinos are brought to the cities, suburbs, and wealthy households in the countryside as domestic help. These domestic helpers are very often young women who must face exploitative conditions. No matter their destination, they are undoubtedly a product of the massive landlessness and joblessness brought about by feudalism in the Philippines.

Feudalism is primarily an agriculture-based economic system where most farmers or peasants don’t own land and are forced to work for a landlord who profits off excessive land rent rates, exorbitant loan interest rates, and very low crop prices, among others. Over decades, this setup has become dominant across the Philippines. In effect, it has left 9 out of 10 farmers landless today and has forced peasants and families to sell their labor to landlords, in urban areas, and abroad.

Equally important to this economic system is the backward haciendero, or feudal, culture needed to maintain it. Oppressive religious practices combined with the lack of access to quality education produces a culture in which people internalize unquestioning obedience and utang na loob (debt of gratitude). It produces a society where exploitation is downplayed as a temporary state worth bearing to prevent any collective resistance and thoroughgoing change. In a feudal society, bahala na (come what may) becomes a guiding principle, just as Eudocia was forced to internalize.

Domestic feudalism also plays a role in the forced migration of millions of Filipinos every year. Along with imperialist interests from countries like the U.S., feudalism helps to maintain an economic structure in the Philippines that is export-oriented and import-dependent. On one hand, agricultural products like sugar and coconuts produced on feudal haciendas (with one of the largest haciendas in the Philippines located in the same province Eudocia hails from), as well as other natural resources like minerals, are exported to other countries. On the other hand, finished consumer goods—like electronics, clothes, and cars—are largely imported and sold to the Philippines at high rates rather than made domestically. This is due to unequal trade agreements with imperialist countries that seek to dump excess products on foreign markets to earn profit. In essence, Filipino peasant farmers who work long days to produce goods that feed and supply the rest of the world face the harsh contradiction of being unable to provide for their own families.

The result? Lack of domestic industry and widespread landlessness—conditions that have pushed Filipinos into poverty, and subsequently out of the country to find work. Facilitated by Philippine laws and institutions, and dictated by foreign demands, Philippine migration has supplied the world with at least 12 million Filipinos, four million of whom are in the U.S., with one of those families being the Tizons. Beyond the reality that Filipinos are forced to migrate abroad due to lack of economic opportunity at home, many are actually trafficked and forced to work in different countries. Indeed, Eudocia is one of hundreds of Filipinos who are trafficked into the U.S. every year as teachers, bakery workers, shipyard workers, and more.

Tizon’s confession opened the eyes of many to an unjust social practice occurring in the Philippines and abroad. It is a practice stemming from feudalism, imperialism, and a government in place that facilitates this exploitation and oppression of its people. This does not exonerate the Tizon family’s abuse and exploitation of Eudocia. But in seeking justice for Eudocia, we should seek justice as well for the millions of Filipinos pushed into poverty and out of the country by feudal landlessness, joblessness, and the lack of opportunities. We invite those seeking to channel their justified rage, sadness, and desire to act to meet with or join a local chapter of Anakbayan-USA or other BAYAN USA organizations near you. Only through collective action and organizing can we ensure that no other person must live their life as someone else’s servant.

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento