Craig Murray’s Jailing Is the Latest Move in a Battle to Snuff out Independent Journalism

MEDIA, 9 Aug 2021

Jonathan Cook – TRANSCEND Media Service

Murray is also the first person to be jailed in Britain for contempt of court for their journalism in half a century – a period when such different legal and moral values prevailed that the British establishment had only just ended the prosecution of “homosexuals” and the jailing of women for having abortions.

Murray’s imprisonment for eight months by Lady Dorrian, Scotland’s second most senior judge, is of course based entirely on a keen reading of Scottish law rather than evidence of the Scottish and London political establishments seeking revenge on the former diplomat. And the UK supreme court’s refusal on Thursday to hear Murray’s appeal despite many glaring legal anomalies in the case, thereby paving his path to jail, is equally rooted in a strict application of the law, and not influenced in any way by political considerations.

Murray’s jailing has nothing to do with the fact that he embarrassed the British state in the early 2000s by becoming that rarest of things: a whistleblowing diplomat. He exposed the British government’s collusion, along with the US, in Uzbekistan’s torture regime.

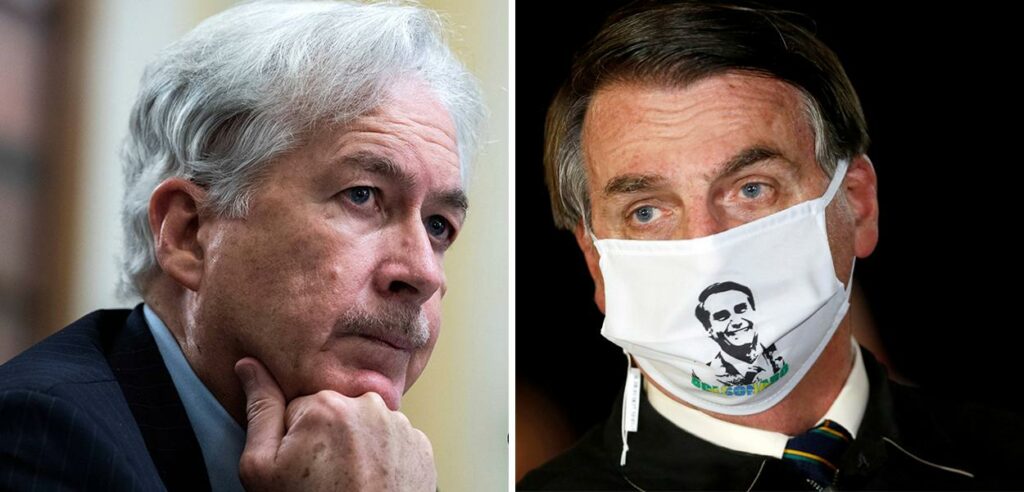

His jailing also has nothing to do with the fact that Murray has embarrassed the British state more recently by reporting the woeful and continuing legal abuses in a London courtroom as Washington seeks to extradite Wikileaks’ founder, Julian Assange, and lock him away for life in a maximum security prison. The US wants to make an example of Assange for exposing its war crimes in Iraq and Afghanistan and for publishing leaked diplomatic cables that pulled the mask off Washington’s ugly foreign policy.

Murray’s jailing has nothing to do with the fact that the contempt proceedings against him allowed the Scottish court to deprive him of his passport so that he could not travel to Spain and testify in a related Assange case that is severely embarrassing Britain and the US. The Spanish hearing has been presented with reams of evidence that the US illegally spied on Assange inside the Ecuadorean embassy in London, where he sought political asylum to avoid extradition. Murray was due to testify that his own confidential conversations with Assange were filmed, as were Assange’s privileged meetings with his own lawyers. Such spying should have seen the case against Assange thrown out, had the judge in London actually been applying the law.

Similarly, Murray’s jailing has nothing to do with his embarrassing the Scottish political and legal establishments by reporting, almost single-handedly, the defence case in the trial of Scotland’s former First Minister, Alex Salmond. Unreported by the corporate media, the evidence submitted by Salmond’s lawyers led a jury dominated by women to acquit him of a raft of sexual assault charges. It is Murray’s reporting of Salmond’s defence that has been the source of his current troubles.

And most assuredly, Murray’s jailing has precisely nothing to do with his argument – one that might explain why the jury was so unconvinced by the prosecution case – that Salmond was actually the victim of a high-level plot by senior politicians at Holyrood to discredit him and prevent his return to the forefront of Scottish politics. The intention, says Murray, was to deny Salmond the chance to take on London and make a serious case for independence, and thereby expose the SNP’s increasing lip service to that cause.

&lt;span<br /> data-mce-type=&#8221;bookmark&#8221; style=&#8221;display: inline-block; width: 0px;<br /> overflow: hidden; line-height: 0;&#8221;<br /> class=&#8221;mce_SELRES_start&#8221;&gt;&lt;/span&gt;

Relentless attack

Murray has been a thorn in the side of the British establishment for nearly two decades. Now they have found a way to lock him up just as they have Assange, as well as tie Murray up potentially for years in legal battles that risk bankrupting him as he seeks to clear his name.

And given his extremely precarious health – documented in detail to the court – his imprisonment further risks turning eight months into a life sentence. Murray nearly died from a pulmonary embolism 17 years ago when he was last under such relentless attack from the British establishment. His health has not improved since.

At that time, in the early 2000s, in the run-up to and early stages of the invasion of Iraq, Murray effectively exposed the complicity of fellow British diplomats – their preference to turn a blind eye to the abuses sanctioned by their own government and its corrupt and corrupting alliance with the US.

Later, when Washington’s “extraordinary rendition” – state-sponsored kidnapping – programme came to light, as well as its torture regime at places like Abu Ghraib, the spotlight should have turned to the failure of diplomats to speak out. Unlike Murray, they refused to turn whistleblower. They provided cover to the illegality and barbarism.

For his pains, Murray was smeared by Tony Blair’s government as, among other things, a sexual predator – charges a Foreign Office investigation eventually cleared him of. But the damage was done, with Murray forced out. A commitment to moral and legal probity was clearly incompatible with British foreign policy objectives.

Murray had to reinvent his career, and he did so through a popular blog. He has applied the same dedication to truth-telling and commitment to the protection of human rights in his journalism – and has again run up against equally fierce opposition from the British establishment.

Two-tier journalism

The most glaring, and disturbing, legal innovation in Lady Dorrian’s ruling against Murray – and the main reason he is heading to prison – is her decision to divide journalists into two classes: those who work for approved corporate media outlets, and those like Murray who are independent, often funded by readers rather than paid big salaries by billionaires or the state.

According to Lady Dorrian, licensed, corporate journalists are entitled to legal protections she denied to unofficial and independent journalists like Murray – the very journalists who are most likely to take on governments, criticise the legal system, and expose the hypocrisy and lies of the corporate media.

In finding Murray guilty of so-called “jigsaw identification”, Lady Dorrian did not make a distinction between what Murray wrote about the Salmond case and what approved, corporate journalists wrote.

That is for good reason. Two surveys have shown that most of those following the Salmond trial who believe they identified one or more of his accusers did so from the coverage of the corporate media, especially the BBC. Murray’s writings appear to have had very little impact on the identification of any of the accusers. Among named individual journalists, Dani Garavelli, who wrote about the trial for Scotland on Sunday and the London Review of Books, was cited 15 times more often by respondents than Murray as helping them to identify Salmond’s accusers.

Rather, Lady Dorrian’s distinction was about who is awarded protection when identification occurs. Write for the Times or the Guardian, or broadcast on the BBC, where the audience reach is enormous, and the courts will protect you from prosecution. Write about the same issues for a blog, and you risk being hounded into prison.

In fact, the legal basis of “jigsaw identification” – one could argue the whole point of it – is that it accrues dangerous powers to the state. It gives permission for the legal establishment to arbitrarily decide which piece of the supposed jigsaw is to be counted as identification. If the BBC’s Kirsty Wark includes a piece of the jigsaw, it does not count as identification in the eyes of the court. If Murray or another independent journalist offers a different piece of the jigsaw, it does count. The obvious ease with which this principle can be abused by the establishment to oppress and silence dissident journalists should not need underscoring.

And yet this is no longer Lady Dorrian’s ruling alone. In refusing to hear Murray’s appeal, the UK supreme court has offered its blessing to this same dangerous, two-tiered classification.

Credentialed by the state

What Lady Dorrian has done is to overturn traditional views of what constitutes journalism: that it is a practice that at its very best is designed to hold the powerful to account, and that anyone who engages in such work is doing journalism, whether or not they are typically thought of as a journalist.

That idea was obvious until quite recently. When social media took off, one of the gains trumpeted even by the corporate media was the emergence of a new kind of “citizen journalist”. At that stage, corporate media believed that these citizen journalists would become cheap fodder, providing on-the-ground, local stories they alone would have access to and that only the establishment media would be in a position to monetise. This was precisely the impetus for the Guardian’s Comment is Free section, which in its early incarnation allowed a varied selection of people with specialist knowledge or information to provide the paper with articles for free to increase the paper’s sales and advertising rates.

The establishment’s attitude to citizen journalists, and the Guardian’s to the Comment is Free model, only changed when these new journalists started to prove hard to control, and their work often highlighted inadvertently or otherwise the inadequacies, deceptions and double standards of the corporate media.

Now, Lady Dorrian has put the final nail in the coffin of citizen journalism. She has declared through her ruling that she and other judges will be the ones to decide who is considered a journalist and thereby who receives legal protections for their work. This is a barely concealed way for the state to license or “credentialise” journalists. It turns journalism into a professional guild with only official, corporate journalists safe from legal retribution by the state.

If you are an unapproved, uncredentialed journalist, you can be jailed, as Murray is being, on a similar legal basis to the imprisonment of someone who carries out a surgical operation without the necessary qualifications. But whereas the law against charlatan surgeons is there to protect the public, to stop unnecessary harm being inflicted on the sick, Lady Dorrian’s ruling will serve a very different purpose: to protect the state from the harm caused by the exposure of its secret or most malign practices by trouble-making, sceptical – and now largely independent – journalists.

Journalism is being corralled back into the exclusive control of the state and billionaire-owned corporations. It may not be surprising that corporate journalists, keen to hold on to their jobs, are consenting through their silence to this all-out assault on journalism and free speech. After all, this is a kind of protectionism – additional job security – for journalists employed by a corporate media that has no real intention to challenge the powerful.

But what is genuinely shocking is that this dangerous accretion of further power to the state and its allied corporate class is being backed implicitly by the British journalists’ union, the NUJ. It has kept quiet over the many months of attacks on Murray and the widespread efforts to discredit him for his reporting. The NUJ has made no significant noise about Lady Dorrian’s creation of two classes of journalists – state-approved and unapproved – or about her jailing of Murray on these grounds.

But the NUJ has gone further. Its leaders have publicly washed their hands of Murray by excluding him from membership of the union, even while its officials have conceded that he should qualify. The NUJ has become as complicit in the hounding of a journalist as Murray’s fellow diplomats once were for his hounding as an ambassador. This is a truly shameful episode in the NUJ’s history.

Free speech criminalised

But more dangerous still, Lady Dorrian’s ruling is part of a pattern in which the political, judicial and media establishments have colluded to narrow the definition of what counts as journalism, to exclude anything beyond the pap that usually passes for journalism in the corporate media.

Murray has been one of the few journalists to report in detail the arguments made by Assange’s legal team in his extradition hearings. Noticeably in both the Assange and Murray cases, the presiding judge has limited the free speech protections traditionally afforded to journalism and has done so by restricting who qualifies as a journalist. Both cases have been frontal assaults on the ability of certain kinds of journalists – those who are free from corporate or state pressure – to cover important political stories, effectively criminalising independent journalism. And all this has been achieved by sleight of hand.

In Assange’s case, Judge Vanessa Baraitser largely assented to US claims that what the Wikileaks founder had done was espionage rather than journalism. The Obama administration had held off prosecuting Assange because it could not find a distinction in law between his legal right to publish evidence of US war crimes and the New York Times and the Guardian’s right to publish the same evidence, provided to them by Wikileaks. If the US administration prosecuted Assange, it would also need to prosecute the editors of those papers.

Donald Trump’s officials bypassed that problem by creating a distinction between “proper” journalists, employed by corporate outlets that oversee and control what is published, and “bogus” journalists, those independents not subject to such oversight and pressures.

Trump’s officials denied Assange the status of journalist and publisher and instead treated him as a spy who colluded with and assisted whistleblowers. That supposedly voided the free speech protections he constitutionally enjoyed. But, of course, the US case against Assange was patent nonsense. It is central to the work of investigative journalists to “collude” with and assist whistleblowers. And spies squirrel away the information provided to them by such whistleblowers, they do not publicise it to the world, as Assange did.

Notice the parallels with Murray’s case.

Judge Baraitser’s approach to Assange echoed the US one: that only approved, credentialed journalists enjoy the protection of the law from prosecution; only approved, credentialed journalists have the right to free speech (should they choose to exercise it in newsrooms beholden to state or corporate interests). Free speech and the protection of the law, Baraitser implied, no longer chiefly relate to the legality of what is said, but to the legal status of who says it.

A similar methodology has been adopted by Lady Dorrian in Murray’s case. She has denied him the status of a journalist, and instead classified him as some kind of “improper” journalist, or blogger. As with Assange, there is an implication that “improper” or “bogus” journalists are such an exceptional threat to society that they must be stripped of the normal legal protections of free speech.

“Jigsaw identification” – especially when allied to sexual assault allegations, involving women’s rights and playing into the wider, current obsession with identity politics – is the perfect vehicle for winning widespread consent for the criminalisation of the free speech of critical journalists.

Corporate media shackles

There is an even bigger picture that should be hard to miss for any honest journalist, corporate or otherwise. What Lady Dorrian and Judge Baraitser – and the establishment behind them – are trying to do is put the genie back in the bottle. They are trying to reverse a trend that over more than a decade has seen a small but growing number of journalists use new technology and social media to liberate themselves from the shackles of the corporate media and tell truths audiences were never supposed to hear.

Don’t believe me? Consider the case of Guardian and Observer journalist Ed Vulliamy. In his book Flat Earth News, Vulliamy’s colleague at the Guardian Nick Davies tells the story of how Roger Alton, editor of the Observer at the time of the Iraq war, and a credentialed, licensed journalist if ever there was one, sat on one of the biggest stories in the paper’s history for months on end.

In late 2002, Vulliamy, a veteran and much trusted reporter, persuaded Mel Goodman, a former senior CIA official who still had security clearance at the agency, to go on record that the CIA knew there were no WMD in Iraq – the pretext for an imminent and illegal invasion of that country. As many suspected, the US and British governments had been telling lies to justify a coming war of aggression against Iraq, and Vulliamy had a key source to prove it.

But Alton spiked this earth-shattering story and then refused to publish another six versions written by an increasingly exasperated Vulliamy over the next few months, as war loomed. Alton was determined to keep the story out of the news. Back in 2002 it only took a handful of editors – all of whom had risen through the ranks for their discretion, nuance and careful “judgment” – to make sure some kinds of news never reached their readers.

Social media has changed such calculations. Vulliamy’s story could not be quashed so easily today. It would leak out, precisely through a high-profile independent journalist like Assange or Murray. Which is why such figures are so critically important to a healthy and informed society – and why they, and a few others like them, are gradually being disappeared. The cost of allowing independent journalists to operate freely, the establishment has understood, is far too high.

First, all independent, unlicensed journalism was lumped in as “fake news”. With that as the background, social media corporations were able to collude with so-called legacy media corporations to algorithm independent journalists into oblivion. And now independent journalists are being educated about what fate is likely to befall them should they try to emulate Assange or Murray.

Asleep at the wheel

In fact, while corporate journalists have been asleep at the wheel, the British establishment has been preparing to widen the net to criminalise all journalism that seeks to seriously hold power to account. A recent government consultation document calling for a more draconian crackdown on what is being deceptively termed “onward disclosure” – code for journalism – has won the backing of Home Secretary Priti Patel. The document implicitly categorises journalism as little different from espionage and whistleblowing.

In the wake of the consultation paper, the Home Office has called on parliament to consider “increased maximum sentences” for offenders – that is, journalists – and ending the distinction “between espionage and the most serious unauthorised disclosures”. The government’s argument is that “onward disclosures” can create “far more serious damage” than espionage and so should be treated similarly. If accepted, any public interest defence – the traditional safeguard for journalists – will be muted.

Anyone who followed the Assange hearings last summer – which excludes most journalists in the corporate media – will notice strong echoes of the arguments made by the US for extraditing Assange, arguments conflating journalism with espionage that were largely accepted by Judge Baraitser.

None of this has come out of the blue. As the online technology publication The Register noted back in 2017, the Law Commission was at the time considering “proposals in the UK for a swingeing new Espionage Act that could jail journalists as spies”. It said such an act was being “developed in haste by legal advisers”.

It is quite extraordinary that two investigative journalists – one a long-term, former member of staff at the Guardian – managed to write an entire article in that paper this month on the government consultation paper and not mention Assange once. The warning signs have been there for the best part of a decade but corporate journalists have refused to notice them. Similarly, it is no coincidence that Murray’s plight has also not registered on the corporate media’s radar.

Assange and Murray are the canaries in the coal mine for the growing crackdown on investigative journalism and on efforts to hold executive power to account. There is, of course, ever less of that being done by the corporate media, which may explain why corporate outlets appear not only relaxed about the mounting political and legal climate against free speech and transparency but have been all but cheering it on.

In the Assange and Murray cases, the British state is carving out for itself a space to define what counts as legitimate, authorised journalism – and journalists are colluding in this dangerous development, if only through their silence. That collusion tells us a great deal about the mutual interests of the corporate political and legal establishments, on the one hand, and the corporate media establishment on the other.

Assange and Murray are not only telling us troubling truths we are not supposed to hear. The fact that they are being denied solidarity by those who are their colleagues, those who may be next in the firing line, tells us everything we need to know about the so-called mainstream media: that the role of corporate journalists is to serve establishment interests, not challenge them.

___________________________________________

Jonathan Cook is an award-winning British journalist based in Nazareth, Israel, since 2001. He is the author of: Blood and Religion: The Unmasking of the Jewish State (2006); Israel and the Clash of Civilisations: Iraq, Iran and the Plan to Remake the Middle East (2008); and Disappearing Palestine: Israel’s Experiments in Human Despair (2008). In 2011 he was awarded the Martha Gellhorn Special Prize for Journalism. The same year, Project Censored

voted one of Jonathan’s reports, “Israel brings Gaza entry restrictions

to West Bank”, the ninth most important story censored in 2009-10.

Jonathan Cook is an award-winning British journalist based in Nazareth, Israel, since 2001. He is the author of: Blood and Religion: The Unmasking of the Jewish State (2006); Israel and the Clash of Civilisations: Iraq, Iran and the Plan to Remake the Middle East (2008); and Disappearing Palestine: Israel’s Experiments in Human Despair (2008). In 2011 he was awarded the Martha Gellhorn Special Prize for Journalism. The same year, Project Censored

voted one of Jonathan’s reports, “Israel brings Gaza entry restrictions

to West Bank”, the ninth most important story censored in 2009-10.

Go to Original – jonathan-cook.net

Tags: Assange, Corruption, Craig Murray, EU, Investigative Journalism, Journalism, Justice, Media, Scotland, UK

Leave a Comment