England’s ‘pingdemic’ is a convenient distraction from the real problem

More people are being pinged because Covid infections are out of control. But No 10 has its head in the sand

- Stephen Reicher is a member of the Sage subcommittee advising on behavioural science

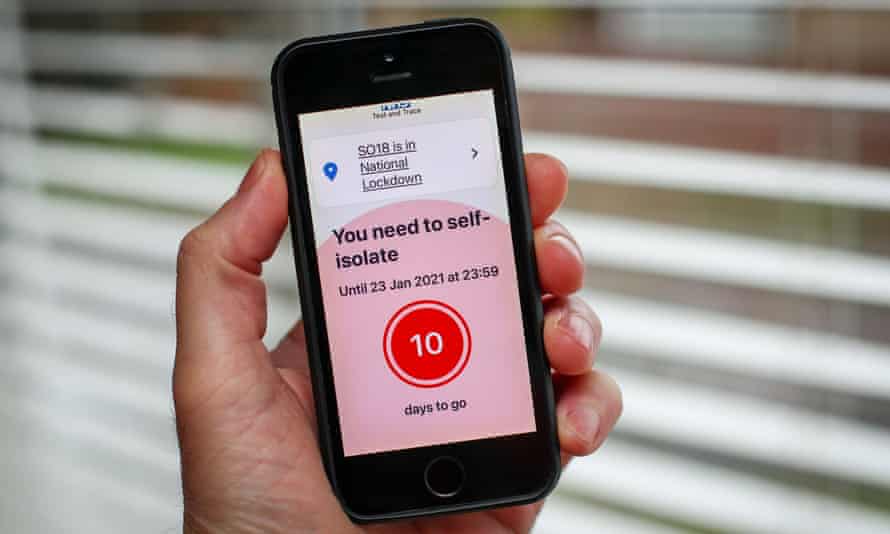

We’re now in the full looking-glass stage of the pandemic, where things seem entirely back to front and solutions are treated as problems. The “ping” of the NHS test-and-trace app has been widely criticised as the cause of disruption for businesses, workers and supply chains. But our problem isn’t a “pingdemic”. A ping simply tells you that you have been in contact with someone who is infected and allows you to do something about it. The problem is the high rate of infection that greatly increases the chances that you will have been in contact with someone who has tested positive – and therefore that you might have Covid too.

Right now we are at a point where one in 75 people in England is infected (up from one in 95 the week before) – even without accounting for the government decision to remove almost all measures on 19 July. While there are many factors are involved, meaning we can’t be sure how infection levels will progress, the health secretary, Sajid Javid, has blithely accepted that cases could rise to 100,000 a day, while some estimates suggest they could reach 200,000.

So, every time you sit on a bus, go to a supermarket or enter a bar, the odds are that someone around you will be carrying the virus. And even though some may now be deleting the app (especially workers who would have to rely on the UK’s paltry sick pay if they had to isolate), almost 27 million of us have downloaded it and are still doing so at a rate of more than 300,000 people per week. So it’s no wonder our towns are now alive with the sound of pinging. The only surprise is that anyone is shocked by what is now happening.

In response, the government has concentrated entirely on the consequences of these alerts. It has created a list of exemptions for workers across industries including food, emergency services and medical supplies, who will now not need to self-isolate if they are pinged. In a particularly dystopian turn, staff who are permitted to attend work after being pinged are legally required to self-isolate when they get home.

By burying its head in the sand and ignoring the cause of all the alerts, the government is creating a vicious spiral that makes things more dangerous: more exemptions lead to more infections, more infections lead to more pings, more pings lead to further exemptions – and further exemptions lead to a further increase in infections.

The only way this approach would make sense is if infections no longer mattered. But they do, in many ways. First, only just over half the population (36.6 million, or 54.9%) are currently fully vaccinated. Nearly half are still unprotected or only partially protected. Second, while the vaccines are effective against serious disease, between 4% and 8% of fully vaccinated people who would previously have been hospitalised after infection still will be. Once there are hundreds of thousands of new infections each day, this will result in a lot of hospitalisations.

The third reason is long Covid. There is still much uncertainty around the details of this disease, but it is undoubtedly a real and growing problem. For many people it has been debilitating, and even relatively mild symptoms can severely affect lives, particularly for young people. Cognitive deficits as a result of “brain fog” that lasts a month can still have catastrophic consequences for those who are working or studying for exams, for example.

Fourth, as many commentators have already pointed out, letting an infection rip through a population increases the likelihood of new variants emerging that could undermine the protection offered by vaccines – and send us back to square one. England’s strategy is therefore not only a menace to its population, but to the entire world. And finally, if case numbers climb further, the disruption to lives and livelihoods will be huge. We’re already seeing the beginnings of this now.

You can only ignore huge numbers of infections for so long. Reality soon catches up, and governments then have to slam on the brakes, imposing restrictions that are far more severe than if they had acted sensibly at the start. That is what happened in the first and second waves. It will probably happen again. There is already talk of reimposing restrictions as summer ends and schools, universities and workplaces become full again. Although the government’s “head in the sand” approach employs the rhetoric of freedom, it actually makes future lockdowns more likely.

The obvious alternative is to take infections seriously and enforce measures to drive them down: masks in crowded spaces, maintaining of social distancing where possible, ensuring indoor spaces are well ventilated and supporting people to self-isolate when they need to (all measures, incidentally, that the government may ignore but a clear majority of the public support). This is how you avoid moving backwards towards more draconian restrictions. This is the real “anti-lockdown” strategy.

And by dealing with the problem of infections, you also remove the issue of “pinging”. If only the government had moved to address the former with the same alacrity as it has the latter. Indeed, its failure to confront rising infections suggests that all the focus on the “pingdemic” is nothing more than a distraction to divert from the real, underlying issues: the government’s failure to address spiralling infections, and its pursuit of policies that exacerbate this problem.

In the end, all the twists, turns, U-turns, complexities and ambiguities about who should or shouldn’t do what when they get “pinged” amount to a great deception – a way of diverting attention from ministers’ failure to do better. For this reason, we should call the situation what it is: a pandemic, not a “pingdemic”.

Stephen Reicher is a member of the Sage subcommittee advising on behavioural science

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento