Why is Italy more populist than any other country in western Europe?

Italy is unmatched in Western Europe in the scale of its electoral support for populists. Michelangelo Vercesi argues that this exceptionality, combined with the strategic adaptation of political entrepreneurs to different territorial political traditions, is a legacy of how the unitary state formed

Populism’s success in Italy

Current electoral polls show that two right-wing populist parties – the League (Lega) and Brothers of Italy (Fratelli d'Italia) – are Italian voters’ most preferred. Overall, four of the five parties with the highest share of electoral support are populist.

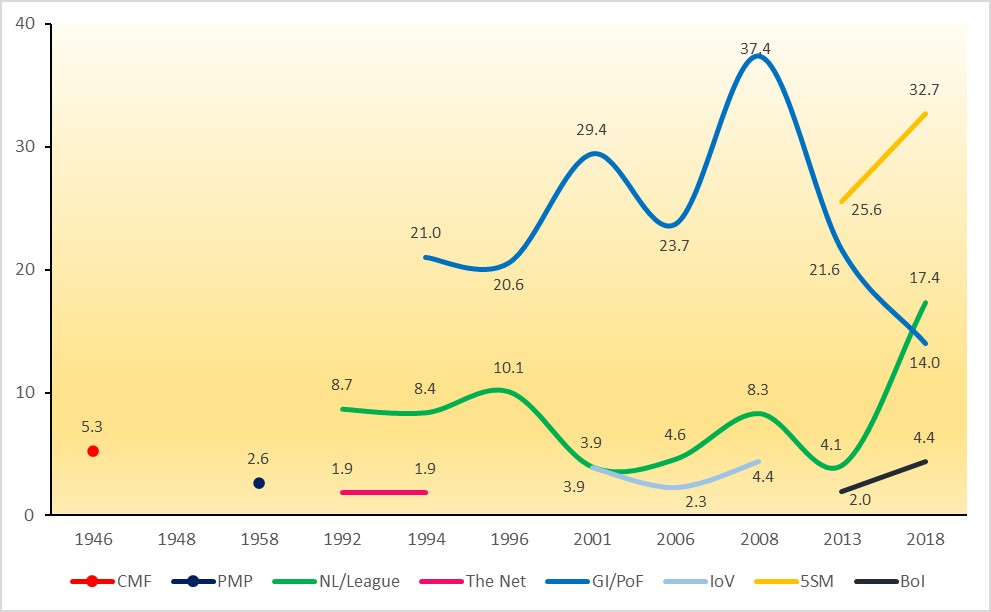

This is nothing new. Electoral support for populist parties has been rising since the breakdown of the former party system in the early 1990s. The aggregate proportion of votes for populists increased from 30% in the general election of 1994 to almost 70% in 2018. No other major West European democracy has witnessed such levels of support for populists.

Italy's aggregate proportion of votes for populists increased from 30% in the general election of 1994 to almost 70% in 2018

Why is Italy ‘more populist’? The answer lies in a combination of widespread anti-institutional and anti-party sentiments, and the strategic response of party leaders.

The deep roots of populism in Italian society

Economic and political crises help explain circumscribed populist outbreaks. Yet they fall short in accounting for the pronounced and persistent inclination of the Italian electorate to vote for populists. The demand for populism in Italy derives from the traditional mistrust towards politics of Italian society. This makes Italian voters more likely to vote for populists.

demand for populism in Italy derives from the traditional mistrust towards politics of Italian society

Such a tradition of disaffection has its roots in the formation of the unitary state of 1861. Following this, the Catholic Church and large sectors of southern elites took a firm position against the new polity and its elites. The original lack of legitimacy of the new state and its institutional weakness initially nurtured anti-institutional and anti-political sentiments in the population. Fascism simply fanned the flames.

Over generations, deep political disaffection, scepticism about party politics, and even dissatisfaction with democracy reproduced themselves. Between them, they created a ‘culture medium’ for the growth of populism.

The role of political entrepreneurs

In democracy, party leaders develop policy programmes and political discourses to maximise voters’ support. Given societal predilections for populism, Italian political leaders have used populist messages as a strategic way to get votes.

These strategies became particularly profitable from the 1990s onwards, when former voters’ political loyalties declined sharply, if not disappeared. Until then, the presence of mass-based party organisations had kept the populist electoral market closed.

These organisations were rooted in society and, in the absence of strong political institutions, gave legitimacy to the Italian political system. When the party system effectively collapsed in the early 1990s, the populist market opened up.

In the immediate aftermath of the Second World War, only two minor populist parties gained representation in parliament. These were the Common Man’s Front and the People’s Monarchist Party.

Meanwhile, in the early 1990s, the Italian party system broke down. Around this time, the birth of the so-called Second Republic resulted in six significant populist parties entering parliament.

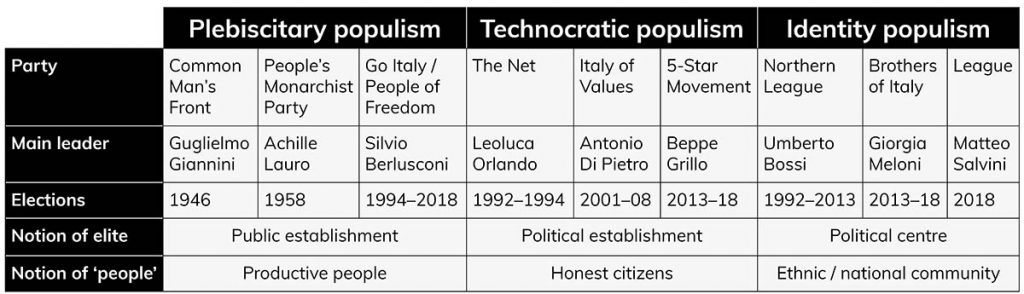

The Northern League (later the League), The Network, Forza Italia (later the People of Freedom), Italy of Values, the 5-Star Movement, and the Brothers of Italy – all these parties have promoted, to varying degrees, anti-elitism, people-centrism and anti-institutionalism.

Lower house % vote share of populist parties in Italy, 1946–2018

Different populist variants in different territorial settings

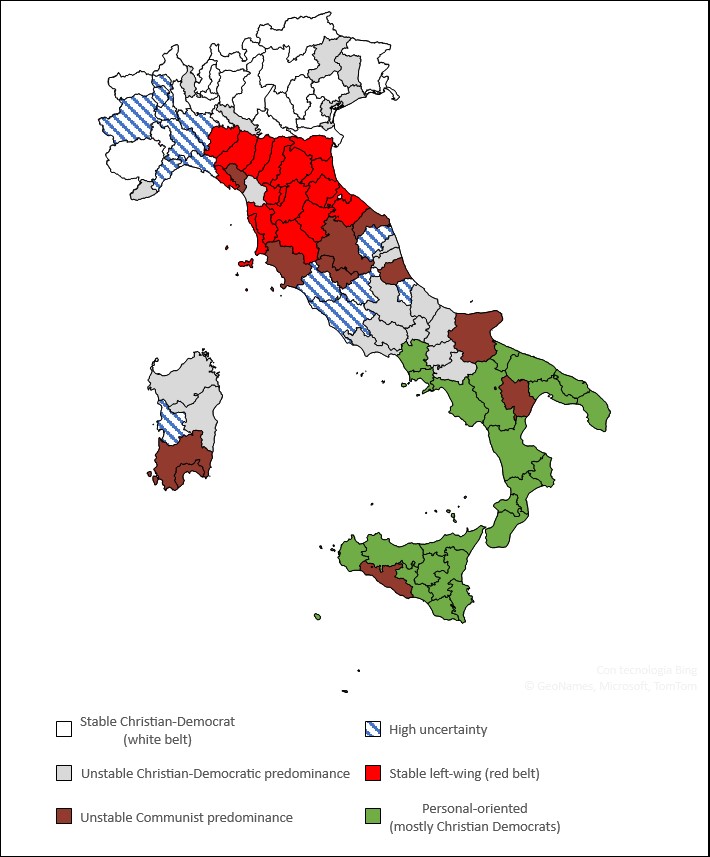

The rise of Italian populism also followed the breakdown of traditional, territorial political differences which had shaped postwar electoral outcomes. In fact, three voter types – ‘of belonging’, ‘of opinion’, and ‘of patronage’ – characterised distinct portions of the territory during the postwar period.

Geographical macro-areas of voting in Italy, 1946–2018

Despite the deep changes in voting from the 1990s onwards, these geographical macro-areas have continued to shape voting patterns. At the 2018 general election, for example, the North voted mostly for the centre-right coalition. The South voted overwhelmingly for the 5-Star Movement, while the former ‘red belt’ (traditionally left wing) shrank further. The Democratic Party won only in the regions of Trentino-Alto Adige / South Tyrol and Tuscany.

In response to these territorial political differences, Italian populist parties have differentiated their populist discourses. In so doing, they have effectively created three main types of populism: plebiscitary, technocratic and identity:

The electoral success of parties of the same type has appeared to depend on territorial variations and ideological orientations. Technocratic populists have adopted centrist positions. We can associate the other two types with (radical) right-wing positions.

In general, populist parties have occupied the political space left empty by the dissolution of pre-1990s governing parties. Technocratic populism has been characterised by a balanced distribution of votes between North and South; plebiscitary populism has received more votes in the South; identity populism has been particularly successful in the North.

Populism for all

We should understand the exceptionally high support for populism and the existence of a variety of populist parties in Italy as the consequence of anti-institutional sentiments within Italian society. The roots of this sentiment lie in the formation of the unitary state.

Political entrepreneurs created populist parties to benefit electorally from disaffected voters

Political entrepreneurs created populist parties to benefit electorally from disaffected voters. At the same time, different types of populist parties with similar ideological positions have proved particularly successful in specific parts of the territory, characterised by distinct traditions of voting behaviour.

Italian populism serves an important purpose of forging a variegated political consensus. It is, therefore, well rooted in Italian democracy, and unlikely to disappear any time soon.

This blog is based on research in Michelangelo's recent Journal of Contemporary European Studies article, Society and Territory: Making Sense of Italian Populism from a Historical Perspective

Leave a Comment