“The origin of SARS-CoV-2 is being seriously questioned”

At a time when researchers are racing against the clock to

develop viable vaccines and treatments, why is it so important to

understand the genealogy of the virus behind the Covid-19 pandemic?

Étienne Decroly:1 After

SARS-CoV in 2002 and MERS-CoV in 2012, SARS-CoV-2, which was quickly

identified as causing Covid-19, is the third human coronavirus

responsible for a severe respiratory syndrome to have emerged in the

past 20 years. We are now quite familiar with this family of viruses,

which circulate primarily among bats, and whose zoonotic transfer

occasionally triggers epidemics among humans. It is therefore crucial to

understand how this pathogen crossed the species barrier and became

easily transmissible from human to human. It is essential to study the evolutionary mechanisms and molecular processes

involved in the advent of this pandemic virus in order to better

anticipate potential outbreaks of this type, and to develop therapeutic

and vaccinal strategies.

In the early weeks of the pandemic, when we knew very little

about the virus, it was very quickly suspected to be of animal origin.

Why was this possibility immediately favoured, and has it since been

confirmed?

É.D.: The zoonotic origin of

coronaviruses, which infect nearly 500 species of bat, was already well

documented from previous outbreaks. In nature, different bat populations

share the same caves, and various viral strains can contaminate the

same animal simultaneously. This situation facilitates genetic

recombination between viruses and their evolution, allowing certain

strains to develop the capacity to cross the species barrier.

Genome sequence comparisons of viral samples from different patients

infected by SARS-CoV-2 have revealed an identity rate of 99.98%,

indicating that the strain emerged in humans very recently. It was also

soon discovered that this genome is 96% identical to that of a bat virus

(RaTG13) collected in 2013 from the animals’ guano, whose sequences

have only been known since March 2020. In addition, one fragment of this

genome proved to be totally identical to another, made up of 370

nucleotides, sequenced in 2016 from samples collected in 2013 at a mine

in China’s Yunnan province where three miners had died of severe

pneumonia.

Furthermore, analyses of other known human coronaviruses show only 79%

genetic identity between SARS-CoV-1 and SARS-CoV-2, and only 50% for

MERS-CoV. Simply put, SARS-CoV-2 is genetically closer to virus strains

that were previously transmitted only among bats. It did not descend

from known human strains and only recently acquired the ability to leave

its natural animal reservoir, which is most likely bats.

If it has been determined that Covid-19 came from bats, why is there still such controversy over its origins?

É.D.: Since

no case of an epidemic caused by direct bat-to-human transmission has

yet been demonstrated, it is thought that the transfer to humans more

probably took place via an intermediate host species in which the virus

could evolve and move towards forms likely to infect human cells. Such

an intermediary is usually identified by examining the phylogenetic

relations between the new virus and those that contaminate animal

species living near the outbreak zone. This method made it possible to

determine that the civet was probably the secondary host of SARS-CoV in

the early 2000s, and the dromedary that of MERS-CoV ten years later. The

discovery, in the genome of a coronavirus infecting pangolins, of a

short genetic sequence coding for the recognition domain of receptor

ACE-2, related to the sequence that allows SARS-CoV-2 to penetrate human

cells, first suggested that a possible intermediary had been found, but

the rest of its genome is too dissimilar to SARS-CoV-2 to be a direct

ancestor.

SARS-CoV-2 could thus have resulted from multiple recombinations among different coronaviruses circulating in pangolins and bats, leading to an adaptation that enables transmission to humans. In this case, a secondary cause of the Covid-19 pandemic would have been contact with the intermediate host, possibly an animal sold in the market in Wuhan (China). However, this hypothesis raises many questions. First of all, the geography: the viral samples from bats were collected in Yunnan, nearly 1,500 kilometres from Wuhan, where the pandemic began. There is also an ecological issue: bats and pangolins inhabit different ecosystems, so it is difficult to imagine how their viruses could have recombined. Most importantly, it has been noted that the identity rate between the SARS-CoV-2 sequences and those from pangolins reaches a mere 90.3%, which is far lower than what is normally observed between strains infecting humans and those contaminating secondary hosts. The genomes of SARS-CoV and the civet strain from which it descended, for example, are 99% identical.

Could you tell us more about the cellular receptor’s

recognition sequence and the mechanism that allows the virus to

penetrate cells?

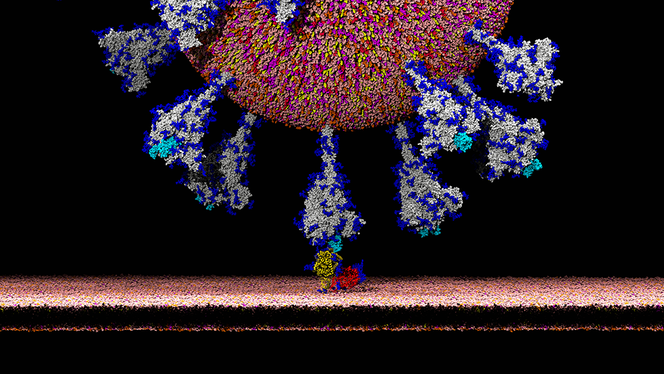

É.D.: That has to do with

the biological characteristics of coronaviruses. Their genome contains

an S gene coding for the spike protein, which enters into the

composition of the envelope and gives the coronavirus its

characteristic “crown” shape. The spike protein plays a fundamental role

in the virus’s infection capacity because it contains a domain, called

RBD, which has the property of binding specifically to certain receptors

(ACE2) on the surface of infectible cells. It is the establishment of

this link that then allows the pathogen to penetrate the cell. The RBD

domain’s affinity for ACE2 receptors in a given species is a determining

factor in the virus’s infection capacity for that species. In humans,

this receptor is widely expressed and can be found, for example, on the

surface of pulmonary and intestinal cells.

Analyses of coronavirus databases have made it possible to determine that the genetic sequence coding for the RBD domain of SARS-CoV-2 is very close to that of the coronavirus infecting pangolins. This observation suggests that the spike protein of the CoV infecting these animals has a strong affinity for the human ACE2 receptor, which possibly enabled that pathogen to enter human cells more easily than the bat virus. However, for reasons mentioned above, most researchers now think that the pangolin probably played no role in the emergence of SARS-CoV-2. The prevalent hypothesis today is that it was more likely a convergent, independent evolution of the RBD domain in both virus strains.

Are there any indications of other candidates for the role of intermediate host?

É.D.: In

zoonoses, secondary hosts are usually found among livestock or wild

animals that come into contact with the human population. In this case,

despite research on viruses found in the animal species sold at the

Wuhan market, no intermediary virus between RaTG13 and SARS-CoV-2 has

been singled out so far. Until one is identified and its genome

sequenced, the question of the origin of SARS-CoV-2 will remain

unanswered. For lack of convincing evidence concerning the last animal

intermediary before human contamination, some sources are suggesting

that the virus could have crossed the species barrier following a

laboratory accident or even be man-made.

Do you think that SARS-CoV-2 escaped from a laboratory?

É.D.: The

hypothesis cannot be ruled out, given that SARS-CoV, which emerged in

2003, has escaped from laboratory experiments at least four times. In

addition, there’s the fact that coronaviruses were a major area of study

in the laboratories near the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak zone, where

researchers were investigating, among other things, the mechanisms

involved in crossing the species barrier. However, at this time, the

analyses based on the phylogeny of the complete virus genomes yield no

clear conclusions on the evolutionary origin of SARS-CoV-2.

There are three main scenarios for explaining how the latter acquired its epidemic potential. First of all, it is a zoonosis. Covid-19 is caused by the recent breaching of the species barrier by a coronavirus. In this case, there must be another virus with greater similarity than RaTG13 in a domestic animal or livestock species, but, as previously mentioned, no such strain has yet been found.

The second scenario is that it could be a coronavirus different from SARS-CoV or MERS-CoV that adapted to humans several years ago and circulated relatively unnoticed until a recent mutation made it more transmissible from an individual to another. To confirm this hypothesis, we would have to analyse virus samples from people who died of atypical pneumonias in the outbreak zone before the pandemic broke out. Lastly, SARS-CoV-2 may have descended from a bat virus isolated by scientists collecting samples, which then adapted to other species during research on animal models in the laboratory – laboratory from which it then accidentally escaped.

Isn’t there a risk that this last hypothesis may uphold the conspiracy theories about the Covid-19 pandemic?

É.D.: Studying

the origin of SARS-CoV-2 is a scientific process that cannot be equated

with a conspiracy theory. At the same time, I would like to underline

the fact that, as long as no intermediate host has been identified, the

scientific community cannot rule out the possibility of an accidental

leak.

As of today, no scientific study has produced any clear evidence to confirm this. Nonetheless, the fact remains that further analyses are needed to reach a conclusion. The question of the natural or synthetic origin of SARS-CoV-2 cannot be made contingent on a political agenda or communication strategy. It deserves to be examined in light of the scientific data at our disposal.

Our hypotheses must also take into account what virology laboratories are capable of doing at this stage, and the fact that the manipulation of potentially pathogenic virus genomes is a common practice in certain laboratories, in particular for studying how viruses cross the species barrier.

Indeed, many conspiracy websites echo the assertions of Luc

Montagnier, who explained that SARS-CoV-2 is a “chimera virus” created

in a Chinese laboratory, a cross between a coronavirus and the human

immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Is this a serious theory?

É.D.: In

any case, it is no longer taken seriously by specialists, who have

refuted its main conclusions. Nonetheless, it is based on an utterly

serious observation that is important for understanding the infection

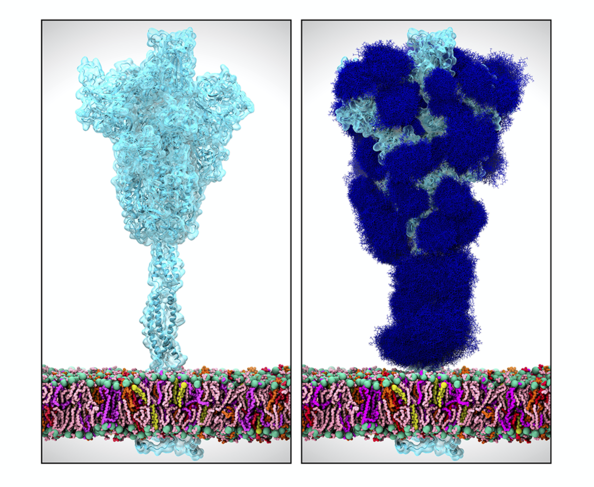

mechanism of SARS-CoV-2: it has been discovered that the gene coding for

the spike protein contains four insertions of short sequences that are

not found in the most genetically similar human coronaviruses. These

insertions probably give the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 exceptional

properties. Structural studies indicate that the first three insertions

are located on exposed domains of the S protein and are thus likely to

play a role in how the virus evades the host’s immune system.

The fourth insertion, which is more recent, produces a site sensitive to furins, protease enzymes produced by the host cells. It has now been clearly demonstrated that furin cleavage of the spike protein induces a conformational change that is conducive to the recognition of the ACE2 cellular receptor. Researchers investigating the origin of these insertions have reported in a pre-publication that these sequences of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein show unsettling similarities with fragment sequences of the HIV-1 virus. Strongly criticised for its methodological shortcomings and errors of interpretation, the article was deleted from the bioRxiv site.

This postulate would have remained insignificant, had it not been revived by Luc Montagnier, winner of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his work on HIV. In April 2020, he claimed that these insertions did not result from natural recombination nor occurred accidentally, but from deliberate gene manipulation, probably in the course of research to develop HIV vaccines. These assertions were once again refuted by biostatistical analyses, which showed that the similar sequences in HIV and SARS-CoV-2 are too short (10 to 20 nucleotides out of a total of 30,000 for the genome) and that the resemblance is most likely coincidental.

Meanwhile, faced with the difficulty of understanding the origin of this pathogen, we have conducted phylogenetic analyses in collaboration with bioinformaticians and phylogeneticists. Their findings show that three of the four insertions observed in SARS-CoV-2 can be found in older coronavirus strains. Our study clearly shows that these sequences appeared independently, at different times in the evolutionary history of the virus. This data invalidates the hypothesis of a recent and intentional insertion by a laboratory of those three sequences.

That leaves the fourth insertion, which produces a furin protease cleavage site in SARS-CoV-2 that is not found in the other viruses of the SARS-CoV family. Consequently, the possibility cannot be ruled out that this insertion results from experiments designed to allow an animal virus to jump species to humans, since it is well known that this type of insertion plays a key role in the propagation of many pathogens in humans.

How can we know for sure?

É.D.: The

SARS-CoV-2 genome is a combinatory puzzle and the recombination

mechanisms of the animal viruses that led to its emergence remain a

mystery. To understand its genesis, many more samples from wild and

domestic species need to be collected. The possible discovery of animal

diseases with a very strong similarity to SARS-CoV-2 would be a key

element for confirming its natural origin. In addition, more in-depth

bioinformatic analyses could reveal possible traces of genetic

manipulation, which would conversely suggest an experimental origin.

In any case, whether the virus is natural or not, the very fact that this question can now be seriously considered calls for a critical review of the reconstruction tools and methods being used in today’s research laboratories, and of their potential use in “gain-of-function” experiments.

But aren’t those the only tools that can help us to understand and combat these viruses and the epidemics they cause?

É.D.: Indeed,

but we must understand that the paradigms of virus research have

changed radically in recent years. Today, any laboratory can obtain or

synthesise a gene sequence. It’s possible to build a functional virus

from scratch in less than a month using sequences available in the

databases. In addition, gene manipulation tools have been developed that

are fast, easy to use and inexpensive. They enable spectacular

progress, but at the same time multiply the risk and possible severity

of an accident, in particular in gain-of-function experiments on viruses

with pandemic potential.

Even if it ultimately turns out that the Covid-19 epidemic is the result

of a “classic” zoonosis, incidents of pathogens escaping from

laboratories have been documented in recent years. One of the best-known

cases is the Marburg virus disease, which originated from contamination

by wild monkeys. The 1977 flu pandemic is another example. Recent

genetic studies suggest that it was caused by the leak of a virus

strain, collected in the 1950s, from a laboratory. More recently,

several such accidental leaks from studies of SARS-CoV have been

reported in the literature. Fortunately, none of them caused a major

epidemic.

International standards require that any research, isolation or culturing involving potentially pandemic viruses, including respiratory ones, must be conducted under secure experimental conditions, with irreproachable traceability in order to prevent any zoonotic transmission. However, accidents can always happen. It is important to consider the potential risk of such experiments, especially if they target gain of function or infectivity.

Are you in favour of a moratorium or ban on this type of research?

É.D.:

I do not advocate an outright ban. The point is not to “sterilise”

research, but to examine the benefit-to-risk ratio more rigorously.

Perhaps a conference should be organised to evaluate the need for a

moratorium or more suitable international regulation.

Considering the risks of infection arising from the techniques used in virus research today, civil society and the scientific community must urgently re-examine the practice of gain-of-function experiments and the artificial adaptation of viral strains in intermediary animal hosts. In 2015, aware of this problem, the federal agencies in the United States froze funding for all new studies involving this type of experiment. The moratorium ended in 2017. In my opinion, these high-risk practices should be reconsidered, and monitored by international ethics committees.

Lastly, researchers in these fields must also be more sensitive to their own responsibility whenever they are conscious of the possible dangers incurred by their work. There are often alternative experimental strategies that can achieve the same purpose while greatly reducing the risks.

Aren’t those strategies already used?

É.D.: In

theory, yes. In reality, we often fall short of the goal, especially

because we scientists do not receive sufficient training on these

issues. And because the climate of competition that reigns in the world

of research encourages fast, frantic experimentation that does not

really take ethical questions into account, nor weigh a project’s

potential risks.

In the master’s programme that I teach on viral engineering, I have been giving, for about ten years, a theoretical exercise which consists in imagining a process that would give HIV the capacity to infect any cell in the body (and not just lymphocytes). While most of the students are able to come up with an effective method for building a potentially dangerous chimera virus, they focus exclusively on the effectiveness of the technique, without ever questioning the potential consequences of its implementation.

My goal here as a teacher is to make them aware of the issues involved and show them that in many cases it is possible to build experimental systems that are just as effective but offer better control of the biological risks. Starting early in the educational process, we need to train future biologists to always assess the risk and social relevance of their research, however innovative it may be.

- 1. CNRS senior researcher at the AFMB (Architecture et Fonctions des Macromolécules Biologiques – CNRS / Aix-Marseille Université) and a member of the Societé Française de Virologie.

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento